Camera location independence#

To determine whether your camera locations should be treated as independent samples or not, consider the following questions. First, are cameras “sharing” the same animals? If there are multiple cameras within an animal’s home range, the answer is likely “yes” and camera locations are not independent samples. Second, from a statistical perspective, are camera locations close enough together in space that there’s a good likelihood that detection at one camera affects detection at another camera? Or if the same camera locations are sampled repeatedly, is the time frame between surveys so short that detection in one time frame affects the subsequent one? If the answers to one of these questions is “yes”, camera locations should also be treated as dependent samples. The answer to these questions will depend on the biology of the Target Species (e.g., how far they move, and their grouping tendency, territoriality etc.), the survey interval and sampling design. For example, Zuckerberg et al. (2020) illustrate how stratified and systematic non-random designs may lead to biases caused by non-independence of camera locations in some cases (Figures 1 and 3). They also show the implications of independent locations on the number of camera locations.

Whether camera locations are truly independent or not is important for several reasons. When locations are treated as independent samples, but are in actuality not, they can lead to biased and erroneous results, with potentially serious implications for species management and conservation. Common biases include narrower confidence limits than “truth” (leading to a false sense of certainty of about the results), and underestimated species richness or other metrics. It is also important to know if camera locations are truly independent if you’re interested in estimating occupancy. Knowing this information helps determine whether you’re estimating “probability of occupancy” (such as when camera locations are dependent) or “probability of use” (when locations are independent – e.g. cameras cover only a portion of an individual’s home range; Wearn & Glover-Kapfer, 2017).

Spatial autocorrelation (i.e., the tendency for sites that are close together to be more similar) may occur when multiple cameras are placed nearby (such as in clustered, paired or array sampling). Spatial autocorrelation is a form of pseudoreplication (Hurlbert, 1984; when observations are not statistically independent but are treated as if they are) and can be problematic because it can artificially inflate or diminish ecological effects. The degree to which this is a problem will depend on the Target Species (i.e., how far they can travel may dictate the distance at which another camera is too near) and the modelling approach. In these cases, users should consider an analytical framework that accommodates autocorrelation to avoid issues of spatial pseudoreplication (Hurlbert, 1984) and false conclusions (Ramage et al., 2013) (e.g., using random effects; Wearn & Glover-Kapfer, 2017] or spatial autoregressive models; Kelejian & Prucha, 1998).

Note that pseudoreplication ((Hurlbert, 1984) can also occur over time (e.g., if camera locations are sampled repeatedly to obtain detection rates as repeated counts, or if the inter-detection interval is too short for a subsequent detection to be truly independent of the first detection).

In some cases, it is advantageous or required to have dependent detections from multiple cameras. For example, spatially explicit capture-recapture require observations of individual animals at multiple cameras to determine activity centres for density estimation. Furthermore, a clustered or paired study design is often useful when estimating density from individually identifiable species (but see McClintock et al. [2013] and Augustine et al. [2016] for single camera approaches) or needing to increase detection probability of rare species when single independent cameras are insufficient (e.g., O’Connor et al., 2017). In the latter case, increasing survey effort (e.g., survey duration, more cameras) may achieve the same goal without leading to issues on non-independent samples highlighted above.

Spatial autocorrelation: The tendency for locations that are closer together to be more similar.

Pseudoreplication: When observations are not statistically independent (spatially or temporally) but are treated as if they are independent.

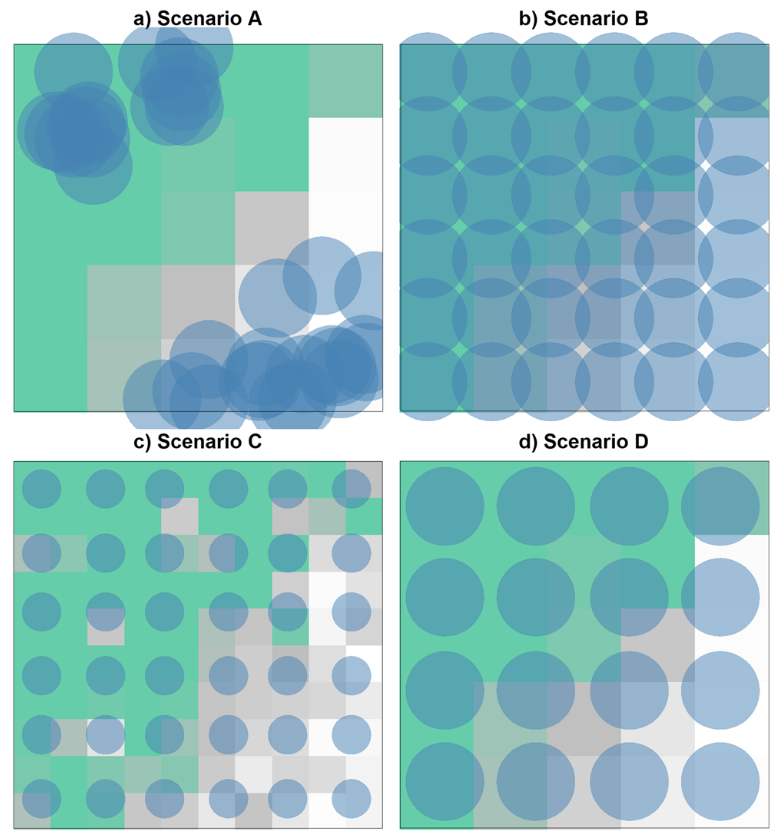

Zuckerberg et al. (2020) - Fig. 1 Four experimental designs sampling species occupancy on a theoretical landscape.

a A simple random sampling scheme demonstrating classical pseudoreplication by failing to adequately sample an important environmental predictor (elevation) operating across the study area. . b A systematic sampling design with strong replication and landscape coverage, but with significant overlapping of landscape buffers. c A systematic design that attempts to avoid overlap by reducing buffering extent. d A systematic design that attempts to avoid overlap by sacrificing sample size.

Zuckerberg et al. (2020) - Fig. 3 Four different sampling scenarios superimposed on maps of probability of occurrence aggregated to different scales of resolution to match the corresponding landscape buffer.

Scenario A implemented a biased sampling scheme with 18 sampling sites stratified by only habitat and ignored the environmental gradient. Scenario B used a regular sampling approach with overlapping landscape buffers. Scenario C used the same sampling sites as scenario B, but with a finer resolution (8-grid cell) to ensure non-overlapping buffers. Scenario D used the same buffer radius as scenarios A and B, but with fewer sampling sites to remove overlapping buffers. Overlapping landscapes were allowed to extend beyond the study region in order to avoid spatial bias towards the center of the landscapes (e.g., mid-domain effect)

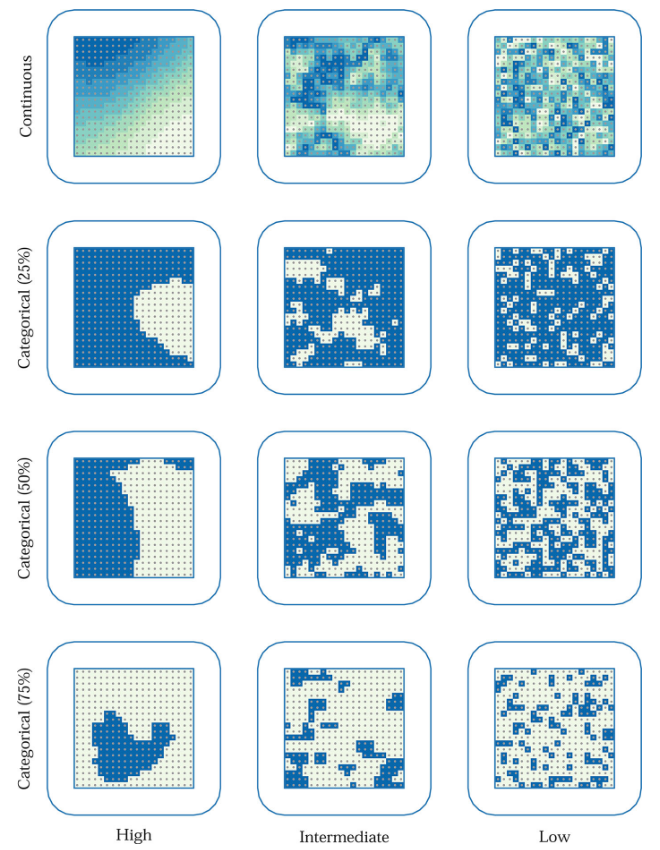

Moqanaki et al. (2021) - Fig. 1 Examples of spatially variable and autocorrelated baseline detection probability (higher = darker blue shading) in grid of detectors (gray dots) centered in a habitat (entire area surrounded by the blue line with rounded corners).

Shown in rows, spatial variation may be continuous or categorical (with different proportion of area in the lower detectability category). Shown in columns, spatial autocorration may vary from high (Moran’s I ≈ 1) to low (Moran’s I ≈ 0). For a detailed description of each scenario, see the main text.

Check back in the future!

Type |

Name |

Note |

URL |

Reference |

|---|

Augustine, B. C., Royle, J. A., Kelly, M. J., Satter, C. B., Alonso, R. S., Boydston, E. E., & Crooks, K. R. (2016). Spatial capture-recapture with partial identity: An application to camera traps. bioRxiv. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/056804

O’Connor, K. M., Nathan, L. R., Liberati, M. R., Tingley, M. W., Vokoun, J. C., & Rittenhouse, T. A. G. (2017). Camera trap arrays improve detection probability of wildlife: Investigating study design considerations using an empirical dataset. PloS One, 12(4), e0175684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175684

Hurlbert, S. (1984). Pseudoreplication and the design of ecological field experiments. Ecological Monographs, 54(2), 187-211. https://doi.org/10.2307/1942661

Kelejian, H. H., & Prucha, I. R. (1998). A Generalized Spatial Two-Stage Least Squares Procedure for Estimating a Spatial Autoregressive Model with Autoregressive Disturbances. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 17, 99-121. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007707430416

Ramage, B. S., Sheil, D., Salim, H. M. W., Fletcher, C., Mustafa, N. -Z. A., Luruthusamay, J. C., Harrison, R. D., Butod, E., Dzulkiply, A. D., Kassim, A. R., & Potts, M. D. (2013). Pseudoreplication in tropical forests and the resulting effects on biodiversity conservation. Conservation Biology, 27(2), 364-372. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23525262

Wearn, O. R., & Glover-Kapfer, P. (2017). Camera-Trapping for Conservation: A Guide to Best-ractices. WWF conservation technology series, 1, 1-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.23409.17767

Zuckerberg, B., Cohen, J. M., Nunes, L. A., Bernath-Plaisted, J., Clare, J. D. J., Gilbert, N. A., Kozidis, S. S., Maresh Nelson, S. B., Shipley, A. A., Thompson, K. L., & Desrochers, A. (2020). A Review of Overlapping Landscapes: Pseudoreplication or a Red Herring in Landscape Ecology? Current Landscape Ecology Reports, 5(4), 140-148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40823-020-00059-4